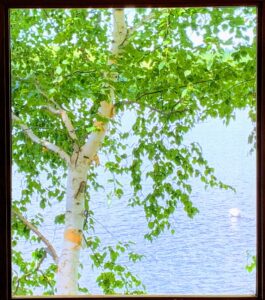

I like to think of them as my trees, two sibling white birches rising out of the bank of Thompson Lake in Poland, Maine. They arch towards the water, just a few yards beyond the screen porch from which I’ve watched them grow since their infancy. I probably shouldn’t refer to them as “my” trees. I didn’t plant them, and hesitate to say I own them, although my wife, Melissa, and I hold legal title to the land from which they sprang as “volunteers.” If I deserve any parental status, it’s only because, year after year, overcoming perpetual vacillation, I let them live.

In June of 1983, long before the birch trees reared their heads, I stood on the screen porch eating a chocolate bar (Cadbury with hazelnuts) taking in the breathtaking view of the lake and debating whether to pay $62,000 to buy a very old house in the Maine woods that I couldn’t afford–a purchase that most who knew me thought made no sense for a single young lawyer living in Manhattan. The house had been the mess hall of a sleepaway camp several miles up the lake, towed across the deep winter ice over a century ago, presumably with mules or horses on some type of sled. Whoever was responsible for this great migration somehow managed to prop the house up on the shore, about fifteen feet from the water, planting it upon an odd collection of stones and logs that continues to serve as a poor excuse for a foundation.

The small house, which came modestly-furnished, had little to commend itself other than where it sat, surrounded by dense woods on a hilly plot of less than an acre, improbably close to the water: it had fake wood panelling, a plywood floor in the living room painted fire engine red, and the only bathroom was wedged into a corner of the kitchen. Upstairs, there were four tiny bedrooms, two of which faced the lake but had no windows–apparently deemed unnecessary for the upstairs of a camp mess hall in those days.

The Big Pine

Overcoming the house’s shortcomings was the dramatic view of the lake, especially from the screened porch. It ran from an enormous pine on my left–about 10 feet in circumference and well over 100 feet tall, but magically nestled into the narrow band of shore between the house and the water; then across the lake to the barely populated woods on the opposite shore and the painterly hills to the northwest; and finally, closer to home again, around the screened corner to another towering tree just a few feet from the porch on my right–this one an enormous old oak that rivaled the pine in height and age.

Thompson Lake, one of the cleanest of the hundreds of lakes in Maine, is located in Poland–a small town that’s home to the now ubiquitous bottled water, a product largely unheard of back in 1983 when I gazed out on the lake and pondered my purchase. By then, the former mess hall sat, as it does now, on the eastern shore of Potash Cove, near the southern tip of the lake, which is twelve miles long and 160 feet deep in places. Thompson has many different personalities and guises, depending on the time of day, the weather and, most importantly, the wind. Often serene and as smooth as a sheet of glass, especially in the early mornings, the lake can turn violent with little warning when storms roll in from the north and white-cap crested waves careen down the lake and pound the shoreline. But on that warm, sunny afternoon in June, the deep blue waves flowed gently from the north, uninterrupted by any human activity on the water.

I was a 31 year old associate of a New York law firm working 65-hour weeks, renting an apartment on Waverly Place in Greenwich village for $400 a month. I’d been to Thompson Lake several times before, to visit my college friends Lark and Annie Madden, always staying in the quaint cabin owned by Lark’s mother just a short walk through the woods from the relocated mess hall. I’d been enchanted by Thompson, reminiscent of the New Hampshire lake featured in On Golden Pond (Squam, an hour away). More importantly, it brought back memories of our family’s annual summer vacations in Maine, among the few we could afford when I was a kid.

Beginning when I was five, we’d piled into our navy Chevy Nova station wagon every August to begin what back then was a ten-hour drive north from Dobbs Ferry, New York, to the village of Port Clyde, where we would freeload off my cousin Carl for a few weeks. Carl, a red-headed Jewish lobsterman–probably the only one in the state of Maine– had grown up in Greenwich Village, fled for Maine when he was 17, married a local Catholic woman with sixteen brothers and sisters, and instantly become related to half the county. A highlight of our trip each summer were my days alone with Carl out on his lobster boat, watching him haul the traps marked by his pink buoys and, as I got older, providing some minimal assistance. Another highlight was the day our families would spend each summer at Jefferson Lake– crystal clear and warm in August–which instilled in me a life-long love of the pristine Maine lakes.

So I was an easy mark when Lark, not only a close friend and gifted musician, but a savvy Boston investment banker, called in the spring of 1983 and convinced me that the former mess hall (on the market due to its long-time owners’ divorce) would be a great “tax shelter,” a thoroughly foreign concept to me at the time. On a whim, I sold my entire $13,000 stock “portfolio,” which constituted the entirety of my assets apart from my clothing, my record collection, and a few pieces of furniture, in order to put down the $12,000 deposit needed to purchase the house. A big factor in this rash decision was that the fledgling People’s Express airline, now long dead and gone, was flying to Portland Maine for $21 each way. And in this pre-9/11 era, the tickets were freely transferable, so I bought two round-trip tickets for most weekends in case I was lucky enough to find a date. Many weekends my second ticket went unused, and I spent the nights out on the dock in my sleeping bag gazing at the stars that saturated the dark Maine sky, especially in August when shooting stars abounded.

Melissa made her maiden voyage to the house on one of our first dates, in June of 1987. It wasn’t long after that first visit before she swept the living room floor, attempting to reach the portion under the large, hideous oval braided rug that had come with the house. She discovered that, unbeknownst to me (and despite my having owned the house for five years), whoever had painted the plywood floor red had painted around, rather than under, the rug. Nevertheless, she immediately fell in love with the house and Maine and, apparently, shortly thereafter with me. We were married eleven months later.

Except for buying a wood stove, I’d given no thought to renovating or refurbishing the house in the years since I’d bought it. I’d settled in with the cheap vinyl-covered furniture that came with the house, and was more concerned with finding dates for my second plane tickets than I was with the decor. But as Melissa and I evolved into a family, so came changes to the house, which graduated from a fluky bachelor pad to a home. In 1990, we gutted the interior, leaving nothing intact but the stone fireplace and the old wooden living room windows. The red plywood floors were replaced with cherry; the fake panelling gave way to knotty pine; and a large dormer upstairs brought windows on the lake side of the house. We added a real bathroom. In the meantime, our immediate and extended families sprouted and flourished. Lark and Annie’s first son, Sam, had been born in 1984 followed by his brother Will in 1986. Melissa and I followed suit: Harris was born in 1991, followed by Tommy in 1996.

My beloved Screen Porch

Throughout all this change, one portion of the house remained virtually untouched: the screened porch, which served as the site of hundreds of dinners with friends and family, as our kids grew from infants into adults. Outdoors, there were constant activities, including King of the Dock contests (which continued until the Madden boys got big enough to throw me off the dock) and fishing (rarely catching) with Lark for landlocked salmon. There were various annual events: Treasure Hunts that sent kids ranging through the woods and across the lake in search of clues; Boss Day–when our kids ruled the roost and could make such demands as ice cream for breakfast, delivered to them out on the float; and Carl’s late summer pilgrimages from Port Clyde, with his three daughters, their children , and a large tub of just-caught lobsters in tow. All the while, and despite this commotion, I spent countless hours sitting in my favorite perch at the corner of the porch–one of two cheap wooden chairs (with floral plastic seat cushions) that came with the house–working on legal briefs and cross-examinations, reading to our young kids, chatting with Melissa, and continually gazing at the ever-changing lake.

The Arrival Of The Birch Trees

It was around the time Tommy was born in the summer of 1996 that the trees made their first appearance on the bank, just to the right of the towering old pine. When I first noticed them they looked more like ideal green sprigs for roasting marshmallows than trees. Standing about 13 inches high and less than an inch around, only their leaves enabled me to identify them as infant birches. I could easily have just pulled them out by hand, and was often tempted to do so. But I didn’t.

The Sibling Birch Trees

Year after year, I watched the toddler birches grow. From tiny green spindles, they graduated to wearing robes of thin brown bark with white speckles, gaining inches and heft each year. I marvelled at their steady climb, but that’s when my years of agonizing–procrastinating–over my trees’ fate–began. While I loved watching the baby trees grow up, I knew I couldn’t rely on them to fly the coop someday, leaving us with our prior delightful empty nest. Instead, as my friend and neighbor Pete kept reminding me, as the birches got older they would obstruct our view. And, as I also knew (and usually appreciated), our extraordinary proximity to the water came with its share of restrictions in the form of Maine’s environmental protection laws and local Code enforcement. Today, for example, a house on Thompson Lake would need to be built at least 100 feet from the shore; ours was grandfathered so long as we didn’t change the footprint. More importantly in my immediate context, I was under the understanding that a healthy tree on the lakeshore that is more than three inches in diameter could not be cut down. And so my consternation increased with each passing year as the girth of my young birches approached the do-or-die mark. I struggled continually with whether to pull the plug on the little friends with whom I’d become enamored, much in the same way I hesitated to kill insects or even mice that weren’t bothering me. It was something about the notion of playing God and snuffing out the life of another that had always given me an uneasy, guilty feeling. Fear that I’d pay a price later.

To further complicate matters, the young birch tree on the left was headed for conflict with the branches of the huge pine tree. I wondered what would happen when that inevitable day of reckoning came. Would the birch tree’s branches forcefully push upwards and break the old pine’s branches? Or would the old man successfully resist, and stunt the growth of its young impatient neighbor?

The time for me to choose whether my trees would live or die was dwindling as steadily they were growing–and gradually developing their coat of classic white birch bark in the process. On the one hand, I was rooting for the little guys and taking some pride in their steady evolution. At the same time, I bemoaned their inevitable intrusion on our view of the lake. In retrospect, perhaps it was my own view from my favorite chair that I worried about. Melissa was less concerned about the view (which would still be expansive) and probably bored with my constant vacillation over the fate of the birches. In truth, I think I was leaning towards wielding the power I still held to put them to death. But then lightning struck. Literally.

Late on a Sunday afternoon at the end of a July 4th weekend, Willard and Irene Stone, our neighbors who lived up the hill on the main road, strolled down to our place and stood out on our dock admiring the lake just a few hours after Melissa, the kids, and I had flown back to New York. Powerful storms can materialize quickly in Maine, and within minutes after the Stones headed back to their farm a violent thunderstorm hit. Walking up the steep dirt road in the downpour, the Stones heard a crash. Lightningning had struck the top of the great pine that stood no more than 10 feet from our house. When Willard returned the next day, he saw that the bolt had sheared off the top 60 feet of the tree, which had fallen straight down along the shore, parallel to our living room windows. The massive weight of the severed top wiped out the shoreline and punctured the roof of the attached boathouse that guests had stayed in that weekend. But it somehow missed the main portion of the house, which fortuitously dodged complete destruction.

By the next summer we’d done what was possible to rebuild the shoreline with rip-rap and a few tough plantings, but now there was an added level of complexity to my little dilemma. Years before, a forest ranger had opined that the venerable pine was suffering from white pine disease and would have to come down at some point. Now, with its head lopped off, I needed to consider again its inevitable, perhaps impending mortality. And so I began to see my budding birch trees not merely as upstart intruders but as important successors. Successors who would live on, after both the pine and I were gone. They were saved.

A Glorious Maine Sunset

I sat and watched as my birches blew past the now academic three-inch threshold. Whether they would live or die was no longer for me to decide. Indeed, other than the ability to do some minor pruning, which I agonized over, their fate was beyond my control. And just like two kids conceived by the same parents, striking differences emerged between the two trees, widening as they matured into young adults. Hatched from the same soil only six feet apart, both are now clothed in the classic white birch bark, with only their newest branches sporting the youthful white-speckled brown. Their teardrop-shaped, jagged-edged signature birch leaves are identical. But contrary to what I would have expected, the left-hand birch– growing up under the shadow of the big pine and thus with less full sunlight then its companion on the right–is somehow far taller and broader; now 20 feet taller and inches thicker than her weaker brother. Perhaps the adversity it faced spurred it to greater heights.

As I did expect, my now full-fledged birch trees have diminished our view, which is nevertheless still a wonder–especially in the evenings as we look out on the lake to the west, through and around them to the glorious sunsets that, even after all these years, continue to excite and transport us. Moreover, in the past few years there’s been a new phenomenon to ponder as I sit in my corner chair and watch the birches grow taller and stronger, while I myself travel in the opposite direction.

The Burgeoning Canopy

The engagement between my left hand birch and the big pine arrived last summer: The upper reaches of the birch have risen into and intermingled with the lower branches of the pine–so far to no ill effect on either. At the same time, my birches broached a new union–this one with the overhanging branches and leaves of the towering oak that stands to their right as I look up the lake. Like Tectonic plates moving slowly but surely towards each other, they’re forming a canopy far overhead; a new frame for the view of the lake from our upstairs bedroom window. Nature at work.

But last summer also brought new cause for worry– a reminder that no matter how big and strong kids get we never stop worrying about them. I noticed in August that a large swath of the left-hand birch’s bark–about 5 inches wide–had been stripped about two-thirds of the way around it’s trunk about eight feet from its base. I was aware that a tree will die if it’s bark is stripped all around it’s girth. Indeed, Melissa and I had recently returned from Botswana where, at every turn we’d seen leafless trees that looked like eery wooden sculptures. They had died after animals had feasted on their bark. As a post on the Quora website explained: “You can kill a tree by girdling it. That is taking a strip of bark off in a complete circle around the tree. This is because you will have strangled the tree, completely cutting off its ability to transport water and nutrients by pulling or cutting away layers of phloem and cambium.”

The Stripped Off Bark

This new unforeseen threat to my birch was not unlike the experience I and so many others have had upon being diagnosed with cancer: one moment you’re working and playing full steam and the next, despite feeling no pain, you’re told you’re on the brink of death. So, as I prayed that the stripping wouldn’t go full circle, I began researching surgical options for repairing damaged tree bark.

We closed up the house, which is heated only by my old wood stove, in early October. Shortly before heading out I climbed down the lake bank and got up close to my ailing birch so I could study the patch of bark that had been stripped away. I was relieved to discover that while the thick white piece of the bark had indeed been stripped and was dangling precariously from the trunk, there was a another, thinner layer of bark–this one a light brown–still intact and firmly bonded to the tree.

My discovery shouldn’t have surprised me for two reasons. The first is that it’s well known that birch bark has several layers. Some internet research revealed that the iconic white outer layer, for which birch trees are known, is actually dead, while the inner layers are alive and carry the trees’ nourishment. The second reason was more personal–and one to which I flashed back as I stood on the bank last October: Forty years earlier, birch bark had saved me during a 100 mile canoe trip on the Allagash River in Northern Maine.

Holed-up in a riverside campsite as night approached in the middle of a torrential downpour, my college roommate and I were drenched, cold and bummed. Things looked especially bleak because all the wood we would have used to make a campfire was also soaked, and our ability to start a fire in the windy downpour was nil. In a stroke of luck, an off-duty forest ranger vacationing with his wife pulled off the river into our campsite. After pitching their tent, the ranger had us collect some birch bark. He spent the next half hour patiently peeling back the soaked outer layer of the bark to get to the dry, paper-thin inner layer–akin to that on my ailing birch–which he cut into narrow strips. We watched in amazement as the ranger then used those strips as the foundation to ignite first some kindling that he’d whittled into toothpicks, and then increasingly larger pieces of wet wood that he gradually added. His blazing campfire warmed our bodies and lifted our spirits in the midst of the continuing storm. And so, suddenly reminded of the magical properties of birch bark, I left our house for the season last October with renewed hope for the trees I’d allowed to live and had come to treasure. The bark’s stripped outer layer was beautiful but, at this point, superficial; it’s the inner layer that counts, and the trees should be fine.

********************************

Much has changed since the birch trees popped out of the earth on the bank of the lake. Just as they’ve travelled from infancy to adulthood before my eyes, so have our children, all now moving on and charting their own ways in this ominous world. Along with the big pine, which has soldiered on looking healthier than ever since having its head lopped off, I’ve been lucky to escape the clutches of some ominous medical crises. Melissa, 29 on her first voyage to Maine and then short on self confidence, is now 61 and has blossomed. Powered by a mixture of passion, judgement, and courage, she has shepherded me through my medical gauntlet, our kids through their own challenges, and served as a trusted lawyer and adviser to friends who have sought her counsel. At the same time, like clockwork upon turning 60, Melissa began experiencing her own relatively minor but humbling health adventures, while occasional gray hairs have cropped up in the midst of her thick red mane to go along with the wisdom that has come with age. Carl, long my image of rugged vitality, still visits but even he is fading.

Our adult birches and children will continue to mature as they face the winds that will inevitably buffet them. At some point in their lifetimes, the old pine and I will depart, incredibly lucky to have had such rich and story-laden lives. The average life expectancy of a birch tree is 140 years. With any luck, my birches will outlive us all.

To read why I believe the common criticisms of Millennials are wrong, click here.

I just love this story, Rich. What a lot of wonderful memories!

Enjoyable read. Puts me in mind of a task my wife assigned me quite a few years back, when we lived in a century-old farmhouse on an acre of land with a wet corner along the northern perimeter. A maple had sprouted next to the foundation of the garage, and when it had asserted itself to a length that encroached on the rear walkway, it was suggested that it needed to be pulled, and I needed to pull it. It came up after some initial stubborn resistance, but Instead of throwing it into the weed pile, I thought I’d tease my wife and plant it, to see if the three-foot branch would take root in the soggy area of the yard and perhaps suck up some of the excess water. I dug a small hole and planted the forked stick, which leaned to one side like a skinny drunkard.

Not only did it take root, it thrived. Within two years, we had a healthy six-foot tree, and within five, a twin-trunked, established maple that eventually grew to thirty feet. It remains as the anchor of that end of that property, and actually did manage to make solid earth of the muddy ground into which it was jokingly inserted.

Thanks Kevin—A great story, and I’m sure your wife expresses are admiration for your judgment and compassion every time you pass by the lucky maple.

I am a retired engineer from western NY. My parents took my sister and me to Boston and to Maine, specifically Bailey Island when we were 7 to about 12 or so. Rented rooms from local Lobstermen and their families. Reading your story brought good memories back. Your writing is wonderful. I enjoy your style. PS my father was a lawyer and a judge in our town and in the area around it. Passed away many years ago but he loved Maine also.

Thanks very much Kathy. It’s amazing how memories of childhood family trips to great places like Bailey Island stick with us for a lifetime.

So beautiful to tell the stories of your life as intertwined with this beautiful little place in the world, and how your special neighbors – the birches – became part of that scene. Love your descriptions and metaphors – vivid word pictures and insights all through. These stories make what I already thought was a wonderful place – even more magical. . .

Love this!