It began on Christmas in Dobbs Ferry, New York when I was about six, which would have been 1958. I woke my sister Debbie before dawn to get a jump on opening presents. Ripping away the wrapping paper, I discovered a book around the size of a comic book: the Trapp Family Recorder Method book. I also unwrapped a soprano recorder. Ignoring the book for the moment, I blew into the recorder without covering any of the holes on the instrument, which produced a loud, shrill whistle – like sound that woke my parents.

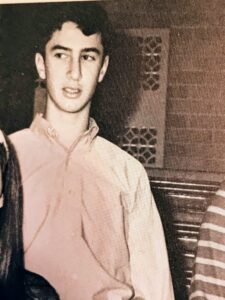

At that moment they may have regretted their choices but, if so, they recovered quickly and, in the weeks that followed, my mother, who could read music and play the recorder, taught me to play the songs in the Trapp Family book. And so began a long, winding journey leading to my current quest as a struggling jazz piano student, a road paved with parental sacrifice undertaken to nurture a budding dabbler. This is not the story of a child prodigy, and music was not my passion as a kid — an honor to which any sport involving a ball held exclusive rights. But music somehow became an important part of my life and has remained so to this day. Like sports, it has taught me lessons that apply beyond playing instruments. And it’s been a bridge that’s helped me connect with strangers and cement bonds with lifelong friends.

The recorder was the launching pad for musical wanderings that took me to various corners of the orchestra. Towards the end of my years at Dobbs Ferry Elementary School I tried my hand at the cello–an absurd instrument for an undersized kid to be lugging between home and school in the years before someone had the good sense to make wheeled cello cases. And I wasn’t any good at it. My one lasting memory of playing the cello in our school orchestra was of an older boy (Jaimie Rickert, I believe) who actually seemed to know what he was doing–placing his bow on top of mine to let me know when I was supposed to stop playing.

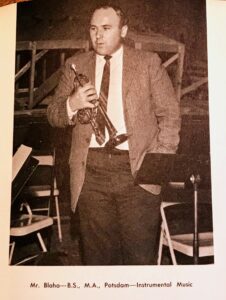

George Blaha

Staying true to my woodwind roots, but for reasons that escape me now, I moved on to the clarinet sometime in junior high, taking lessons in school from George Blaha, our music teacher, orchestra and marching band leader. Mr. Blaha taught kids almost any instrument they chose to play. He was one of those rare individuals you come across too infrequently who don’t seem to have a bad bone in their bodies. Balding and a little heavy-set, but by no means obese, Mr. Blaha had an oval face, an infectious smile, and infinite patience–which he certainly needed to teach the likes of me and the other budding “musicians” who shared meager talent and even less inclination to practice. Unlike Robert Preston’s fraudster character in The Music Man, Mr. Blaha trained and led a real, albeit not very good, small-town orchestra and marching band.

The Piano–Round One

When I was around 11 we moved from our small two-bedroom garden apartment on Beacon Hill to the small three bedroom apartment right next door so that Debbie and I could have separate bedrooms. A major step up in the world for our family at a time when I remember my dad saying that if he “could make $20,000 we’d be in the middle class.” Debbie got the larger room, which soon housed an old upright piano, and our lessons with Uncle Henry.

Uncle Henry was perhaps the dullest adult I’d ever encountered. He had married my great-aunt Bessie, whose first husband had died young. There was nothing striking about Uncle Henry other than the smell of the sardine sandwiches he ate each week as he sat next to me on the piano bench. A slightly chubby man with curly gray hair, Uncle Henry lumbered stiffly with a limp. He spoke in a soft, slow monotone. He wasn’t unkind, but everything about him seemed boring and humorless.

Relative to my mediocre ability, I was a good sight-reader in those days, able to read and play the treble and bass lines of a reasonably easy piano score with little difficulty, a skill I put to full advantage in order to minimize my practice time. Unlike me, Uncle Henry practiced from morning to night when he wasn’t teaching. Literally. At some point in the early 1950’s, Bessie had bought a summer house in the tiny Maine village of Tenants Harbor, following her son, Carl, who had abandoned Greenwich village and college in order to become a lobsterman in the even tinier village of Port Clyde, five miles down the peninsula. Beginning when Debbie and I were four and five, our family piled into our navy blue Chevy Nova station wagon every August and made the 12 hour drive north in order to freeload off Bessie and Carl. Henry had an iron clad routine: After breakfast each morning he placed a stack of music scores on one of two old baby grand pianos in their cluttered living room. One day Chopin, the next Beethoven, Brahms the following day. He then played them cover to cover, stopping only to eat one of his smelly sandwiches at lunch.

At some point, Bessie and Henry abandoned Greenwich Village and settled permanently in Tenants Harbor. Henry kept up his routine for more than a decade after Bessie died, well into his 90’s, leaving the house only once a week to buy groceries. I made annual pilgrimages to visit my cousin Carl with friends and, later, with Melissa and the kids, all of us spending a day on the ocean watching wide-eyed as Carl hauled the lobster traps. At Carl’s request, we always stopped in Tenants Harbor for 15 minutes to pay our respects to Henry, usually on the way home. Henry was as drab and boring as when we were kids.

Although I’m a chronically curious person, prone to striking-up a conversation and learning something fascinating about the life of virtually any stranger or friend, I never discovered anything interesting to discuss with Henry. I now know I never tried. Last summer, as I chatted with a now elderly Carl on our screened porch (also in Maine), he told me that Henry was in one of the first units to storm the beaches of Normandy on D-Day. I felt like a dope, and still do…how much I missed and would have loved to hear! Henry’s heroic ordeal was likely the source of his limp and may have prompted his escape into the piano; a search for peace in the music he played so well.

Our piano lessons with Uncle Henry spanned just a few years, but left me with some familiarity with classical music, including some of the simplest Bach, Mozart and Beethoven pieces, and an ability to read music. I didn’t realize then that a perennial seed had been planted that would continually draw me back to the piano. I can’t describe that seed other than to say that it felt satisfying and soothing to make music that sounded good, at least to my ears. But that seed would lie dormant for several years. In the meantime, I resumed my orchestral career.

The Oboe Years

Having by no means mastered the clarinet, I moved on in junior high to tackle the oboe. While it’s extremely hard to play any instrument well, the oboe — a double-reed woodwind instrument with no mouthpiece–is considered particularly difficult, probably because it may be harder than most instruments to play even poorly. I’m not sure what drew me to the oboe. It might have been its featured role as the duck in Prokofiev’s Peter and the Wolf. It might have been just one facet of a teenage quest to be different and stand apart from those who played such “pedestrian” instruments as the clarinet, the trumpet or the flute (which, in any event, was just for girls like Debbie in those days).

An Intrepid Oboe Player

The best thing I can say about my tenure as an oboist is that it was a testament to my parents’ devotion. It began with their purchase of the oboe, which wasn’t cheap and, I later realized, a luxury they could ill afford. And even with the instrument in hand, getting to the starting gate on the oboe was no simple or inexpensive matter.

The “reed” thru which one plays an oboe consists of two narrow pieces of cane that must be carved by hand until literally paper thin so as to yield the oboe’s unique sound. To procure the reed-making supplies, my dad took me on the train from Dobbs Ferry down to what was then Manhattan’s Music Row. One of New York City’s iconic disappearing districts – 48th street between 6th-7th Avenues – was lined in those days with music stores specializing in different types of instruments. We went to Lynx & Long, where my dad shelled out even more hard earned dollars to buy me the various accoutrements needed to make oboe reeds–a special carving knife, cane, thread for binding, tubes, and jeweler’s screwdrivers for fixing and adjusting the oboe. And, because I didn’t have–and never got–the hang of carving decent reeds, he also bought me pre-made reeds, which are what I actually used.

Then there were the lessons. Teaching the oboe was beyond Mr. Blaha’s prodigious reach, and my parents took turns driving me to Tuckahoe, on the other side of Westchester, for lessons that put them further in the hole and killed half of every Saturday. They never let on that they were strapped for money or that my musical dabbling was imposing any kind of burden on them. Looking back, I’ve wondered why my parents sacrificed so much to nurture a kid who obviously was going nowhere in the world of music and wasn’t even passionate about it. What was the point? Perhaps this was an example of parents sacrificing to give their kids opportunities they never had. Perhaps a way to help me develop into their idea of a “well-rounded” kid with an appreciation for culture. Of one thing I’m confident: none of us harbored any illusion that playing the oboe would burnish my resume and land me a spot in the Ivy League (a remote place where nobody in our high school graduating class of 125 would venture). That wasn’t on our radar screen. I was just living in the present, focused on making the basketball team, getting my driver’s license the minute I turned 16, and girls.

Practicing less than I needed to, I limped along with my private oboe lessons for a few years while continuing to play in our high school orchestra. Although I would have preferred to be outside shooting baskets, throwing a football, or hitting a baseball, playing in the orchestra under Mr. Blaha’s benevolent baton was fun. Our concerts, played to an audience of fawning parents, brought some of the same excitement as playing a Friday night home basketball game before a cheering crowd. Unlike sports teams, however, which despite the importance of teamwork depend heavily for success on standout individual performances, playing in the orchestra was a lesson on blending in—listening carefully to others, moderating our individual volumes, and playing in time with the orchestra. Our success or failure hinged on our collective performance, not on whether one of our players made a buzzer-beating shot or hit a clutch home run to win a game. Orchestras don’t measure individual batting averages or confer Most Valuable Musician awards.

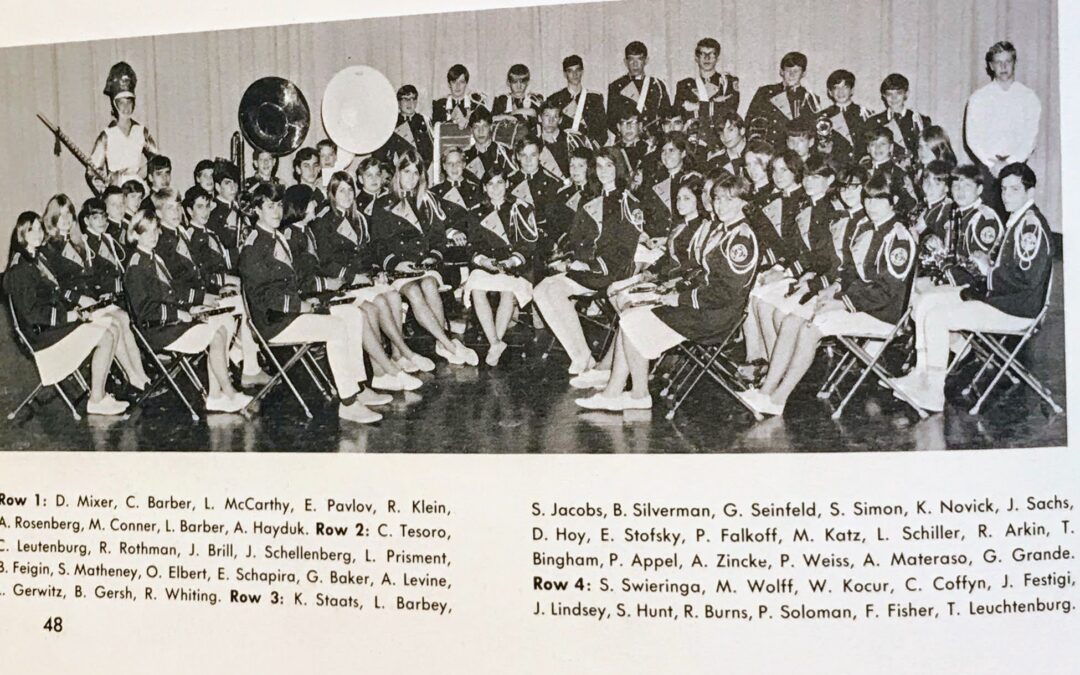

During football season, our school orchestra switched gears and morphed into a marching band (pictured above), complete with navy blue uniforms. We played the school’s fight song and a few other tunes to bolster the football team that my otherwise permissive dad — who worked in the accident and health insurance business — wouldn’t let me play on. It didn’t take long for me to learn that the oboe was a poor fit for a marching band. With no fixed mouthpiece, attempting to march and play at the same time resulted only in broken reeds and bleeding gums. My solution was to do the marching part without the playing, until I was outed by some little kids. Running alongside the band before a sunny Saturday afternoon home game, one of them shouted to his friends: “Hey, this guy’s not playing!” His pals soon joined in: “Why aren’t you playing anything?” And then: “He’s faking it!” By the next game I’d retired the oboe for the season and taken up the cymbals, playing a starring role on the crescendo of the Star Spangled Banner.

On to the Chorus

My musical career took a sharp turn in my senior year of high school when Mr. Blaha changed gears and took the reins of our choir. Many of his disciples, me among them, followed. Mr. Blaha welcomed us regardless of whether we could sing, but moved swiftly to camouflage the weak links by means of strategic placements. He had me stand next to Timothy Riss, the president of the chorus. He told Timothy to angle in my direction and directed me to mimic, as best I could, whatever came from Timothy into my left ear.

I last saw Mr. Blaha when I went back to visit the high school a year after I’d graduated in 1970. With his characteristic twinkle and big smile, he put his arms on my shoulders, looked into my eyes, and said: “You know Rich, we haven’t had a voice in the chorus like yours since you graduated!”

Mr. Blaha’s star didn’t shine for long enough. He was killed in a car crash in June of 1977. At our 50th Dobbs Ferry High reunion, originally scheduled for September 2020 (now lost to the pandemic), I’m sure we would have exchanged fond memories of George Blaha, who, for little money and no fame until his untimely death, taught so many kids like me to play instruments, play together, and appreciate music — even if none of us went on to play for the Philharmonic or get into Harvard on a music scholarship.

Back to my Roots

Entering Tufts University, I left the oboe behind but packed my alto recorder, a constant companion throughout my college years. I spent countless afternoons and late nights tagging along with friends strumming guitars and singing. Always playing by ear, I was able to sound out the melodies of most songs and, with some missteps tolerated by patient friends, improvise during the vocal interludes. My recorder also came along as I ventured out alone, hitchhiking the country and rambling around Europe, accompanying kids playing guitars and singing songs known around the world. My childhood instrument turned out to be a great connector– solidifying lifelong bonds with good friends and serving as a means to meet and have fun with strangers — as well as providing comfort and satisfaction during lonely times. A small but constant testament to the power of music to unite and nourish.

Although my piano lessons with Uncle Henry had by then faded into distant memory, I often sat down when I stumbled upon a keyboard. As with the recorder, I played by ear, sounding out songs to which I knew the melodies. Dylan’s Just Like A Woman, Paul Simon’s Old Friends, and Try to Remember were a few of the tunes to which I often returned. I also loved to improvise. But because my knowledge of chords was paltry, I was like a lousy artist painting everything in the same dull shade of brown — a frustrating barrier I returned to tackle much later in life.

***********************************

I don’t know whether the scarce dollars my parents shelled out ended up being worth it to them. But I can say that thanks to their sacrifices, Mr. Blaha’s patient guidance, and the availability of a music program in our small-town public school, I developed a love of music, which became a rich part of life and provided lessons that extended beyond music.

Extensive research has documented the value of musical instrument training for numerous aspects of child development—including increased reading and math skills (not in my case), spatial and nonverbal reasoning (some would say ditto) and, not surprisingly, fine motor abilities. Statistics indicate that schools with music education programs have higher attendance and graduation rates, among other benefits. Unfortunately, in some parts of the country — notably New York City, music programs have been among the first victims of the all-to-common cuts to public school budgets. The inevitable budget cuts flowing from the pandemic will only increase the bleeding.

Aside from my occasional dabbling on the piano, my own musical career was suspended for four decades by an all-consuming job and kids. I’ll return in Part II to talk about the mountain of jazz piano I’ve been attempting to slowly climb since, at the age of 61, cancer limited my legal career and music emerged for the first time as a major focus of my life.

Photo Credits: Dobbs Ferry High School Yearbook, courtesy of Jim Lindsay

Well written, enjoyable piece! It was especially heartwarming to read your comments about my dad, George Blaha. I was 16 when he died, so learning about him and his influence on others provides me with valuable perspective on the teacher, colleague, and friend he was. Thank you!

Kathy, I know that over the years, you’ve heard over and over again what a wonderful influence your dad was, in addition to being a remarkable man, but even after hearing it a thousand times, that doesn’t cover it. Fifty years later, he’s the one who stands out for all of us fortunate to have been in his orbit. To this day, I love him.

As always, I love this humorous, insightful recollection of an important theme in your life, and sincere testament to the devotion of the music teachers and your parents who made it possible. Like you, my attempt at playing a difficult instrument (violin) ended in defeat, but nonetheless enriched my life by creating a deeper appreciation for people who can. On the other hand, you certainly mastered the recorder. I remember many evenings over the years when you would play – often outdoors in a beautiful place. It is a perfect instrument to play out in nature, both for its portability and clear simplicity – almost like a bird song. Being from Kansas and the Land of Oz, my favorite has always been your lovely rendition of “Somewhere Over the Rainbow” (not an easy song to play!) which makes me tear up. Loved this piece – can’t wait for the piano section!

Stunning memory, Richie. Hard pressed to remember anything more than a paragraph long memory of elementary school mediocrity.

You may recall that my sun is a singer, but not a player (let that pass.) For his high school graduation we bought him a guitar that he had a brief relationship with during college. A bit more than a one date affair, it never blossomed, and continued not to continue. Then came Covid where joyful stories are few. He is now a guitar playing fool, picking up a couple of songs a week, and now has a life long companion to accompany his voice.

Me……..still making excuses for not going to school on clarinet lesson days.

Wonderful reflection on music in our lives Richie. And it elicited yet another parallel in our winding paths together.

Like you, I grew up in a house where music was part of the decor. Sound tracks from My Fair Lady, South Pacific, Flower Drum Song filled our home. My parents ventured into NYC on many Saturday nights to hear Leonard Bernstein conduct the NY Philharmonic. Once they took me.

We had a piano and my parents expected their three children to take piano lessons. I resisted. My 8-yr-old self didn’t want to take any time away from becoming a professional baseball player. Leonard Bernstein didn’t stand a chance against Mickey Mantle and Yogi Berra.

But my mother insisted and assured me that if I took lessons for one year she would not again deflect my career path. The deal was struck and we each kept our end of the bargain.

Baseball continued to dominate but I did take up percussion, maybe thinking that beating on timpani skins was kind of like trying to knock the skin off of a baseball.

For the next 2 decades music was for me a spectator sport, but what a game! From seeing the Jefferson Airplane rock the Fillmore East until 2 am to Woodstock where time was irrelevant, it’s been a glorious ride.

But seeing the musical talent in my Tufts friends, including you sir, inspired another go at participation, and in 1977 I had the good fortune to have enough money to buy an upright piano, have a house big enough to put it in, and have a roommate by the name of Eddie Roberts.

Never before or since have I known someone who could do what Eddie could do – hear music and then immediately play it, sight unseen. He heard notes and cords by name. He couldn’t teach me to hear like him, but he could teach me how to play cords and replicate music, and he did. And some of those 8-yr-old brain cells started firing again.

And now more than 4 decades later, as I sit behind my grand piano in my house in the middle of the deep woods, playing the songs I love, to no one but me (you’re all welcome), I thank my mother and Eddie who, like Mr. Blaha, left us too soon but left us so much.

Tom–the main difference between you and me is that while you wanted to be a baseball player, until the age of 25 I planned on playing in the NBA. When I was interviewed for a job at the law firm where I’ve spent my whole career (not unlike you at your engineering firm), the first question was: “Why did you want to become a lawyer?” And my answer: “If I was 6’8″ I wouldn’t be here.” More importantly, what a wonderful tribute to Eddie–and totally well-deserved and accurate, as all who knew him would agree.

Rich, you think you know a family, yet there’s always something to learn. I so enjoyed reading the evolution of your musical journey, along with the tidbits I don’t remember or never knew. I do remember always being envious of Debbie that she had gone to Maine and I hadn’t, and although I remember you and your oboe really well, never knew what you went through with bleeding gums and “faking it”. So much fun to read about. Aside from all that, though, your beautifully written piece struck such a chord (no pun intended), not only because it was also part of my shared experience, but because the ability of music to weave the pieces of our “being” together is so cathartic, and ultimately, a tonic for the soul. (And on a side note, though I tend to be camera shy, I would’ve really liked to be in that band picture for posterity’s sake…maybe I was out sick that day.)

Richie, this is a very funny and warm remembrance. I remember quite well listening to you, Lark, Annie, and Eddie (et al) play beautiful music. I tried playing harmonica, but had a tin ear. I used to say that you would forget Paul McCartney while listening to Lark sing Blackbird. Annie still does the most beautiful version of Tupelo Honey that I have ever heard. When she sees me, she sings a verse quietly and sweetly to me. Such a treat! Eddie was a sweetheart and it came out in his piano playing. He would smile, his blue eyes would twinkle and nectar for the ear would emanate from the piano. I never knew anything about recorders until I heard you play one beautifully. I also like oboes for the same reason you do.

When people ask me whether I play an instrument, I tell them that I play a turntable, a CD player and an iPod. I tried playing the drums in grammar school. I wanted to play a drum kit in a rock band. My father did not agree that was appropriate music. Hence, there was no drum kit for me. My only claim to fame was playing the cymbals. The band director wanted someone to play cymbal crashes for a John Philip Sousa song. He asked all of us in the percussion section to play as loud as we could. Most demured. I smashed the cymbals together with all of my strength. What did I have to lose. Plus, I was never shy. I was hired on the spot. It was fun to make such noise for a short while. I quickly went back to my records. Besides, I bought my first record in 1957 and never stopped. I couldn’t tolerate my playing terrible music while learning. I still do a lot of listening. I look forward to hearing you play jazz piano soon. Be well and safe!