Photo Credit: Peter Lübeck

A feature article in the September 21st edition of the Wall Street Journal entitled For a Truly Indulgent Vacation, Fly Solo, Nina Sovich reported that although “[o]nce, only intrepid travellers vacationed alone,” today “solo travel has shed its stigma and moved into the mainstream.” The article chronicled how high-end “hotels, cruises and tour operators are easing the way” and that “in these hyperconnected times, you can be alone but hardly lonely.” The proof: there are “more than 5 million posts with #solo-travel on Instagram.” Travelling solo today means something very different than when I roamed Europe forty-five years ago and myriad other young people traipsed around this country and the world on their own. I’m not sure whether anyone would want to recreate that experience now–and they probably couldn’t if they tried. This is the story of a solo journey in an untethered era, very different from the hyperconnected times we all live in today.

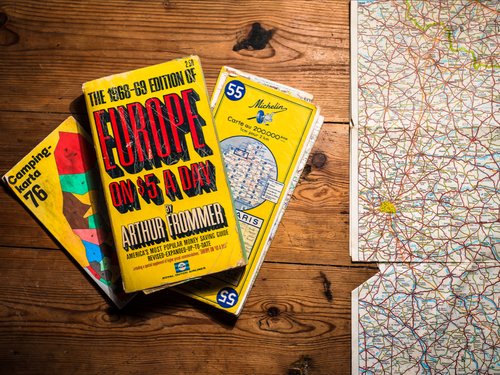

I headed for Europe alone in June of 1974 shortly after graduating from college, armed with a copy of Europe On $5 A Day, a Eurail pass, $1200 I’d earned working in a butcher shop during vacations, and my alto recorder–an instrument my mother taught me to play when I was six. With no itinerary or reservations, my only “plan” was to visit a bunch of countries, most to be determined later–sleeping on overnight trains, in youth hostels, or at cheap hotels when there was no good alternative– starting in London and flying home from Rome six weeks later. I did manage to visit ten countries and take in many of the iconic sites along the way. But it’s not the sites that stood out then, or what I remember now.

With no shortage of friends, I’m not sure why I went alone–perhaps just an attempted show of independence. Having previously hitched across the country solo, I should have known this jaunt wouldn’t be all fun and games, but I may well have forgotten the lonely times that were part and parcel of travelling alone. Particularly in those days, the lows could be hard for a twenty-two year old traveling far from home with no cell phones, email, or Skype to instantly reach family or friends for advice or assistance in jams, or just some comfort. But those low times were often quickly washed away by the highs associated with being able to choose where and when to go based on my own spontaneous whims; making connections in odd ways and having fun with people from each country I landed in; and continually stumbling into and through experiences–some exhilarating, some near disasters–that would never have happened had I been occupied with–and distracted by–a traveling companion while walking the streets in a new city, eating together in restaurants, or discussing the Mona Lisa at the Louvre. It’s these off-the-beaten path experiences, particularly the comical and in some cases bizarre, that remain in view these many years later.

My round trip plane ticket departed from Montreal, the cheapest fare available. After spending a few days at a London youth hostel, I caught a crowded overnight train to Edinburgh. Lucky to be myself, I found the last seat in a compartment that resembled those in the old Basil Rathbone-Sherlock Holmes movies–joining two women and one heavy-set man, all English, all older than me. With little in common, we bonded over our cigarettes and chatted through the night. I forget what brand I was smoking in those days–I’d graduated by then from Tareytons, Parliaments, and Newports, probably to Winstons or Marlboro’s. The woman sitting across from me, a bookkeeper with shoulder-length brown hair wearing, rectangular glasses, and an olive green dress, was smoking “Rothmans”–my namesake, and an iconic English brand. Whenever one of us reached for a cigarette in our own preferred pack, we politely offered one to the others. Not wanting to insult anyone else’s taste, I never declined, nor did my companions. I got off the train in Edinburgh at around 6:30 in the morning, exhausted and nauseous from the chain smoking all-nighter.

I fell in love with the Scottish people immediately. Peering through the window of a small coffee shop, I was downcast when a short, heavy-set elderly woman with her gray hair in a bun, wearing glasses and an apron, emerged and said “I’m sorry son, but we don’t open until 8.” After taking in my disappointment, however, along with my bloodshot eyes and the large backpack I was lugging, she said, in a heavy Scottish brogue I was hearing for the first time: “Why don’t you come back in twenty minutes and I’ll see what I can do for you.” I did that, to the minute, and she cooked me a big breakfast of Scottish bacon and eggs.

After finding a cheap hotel, I spent the day wandering around Edinburgh and then, at night, caroused the Royal Mile, home to more than 500 hundred pubs at the time. I sampled a few before landing in a small, crowded place with long rough-hewn wooden tables and low ceilings. It was shortly before 10 pm, when all the pubs were required by law to stop serving. Sitting at a table with some friendly strangers, at around 9:45 they made a mockery of the 10 pm deadline by filling the table with “boiler makers”–pints of Tartan Special (beer) along with shots of whiskey (single malt “scotch”). Not a big drinker, I stumbled out of the pub an hour or so later and headed in what I thought was the direction of my hotel. Just to be sure, I asked an old man (probably around my age now) to confirm that I was on the right track. “I’m afraid you’re walking in the wrong direction lad. Come with me.” Ignoring my protests, he insisted that Edinburgh–the safest city I’d ever been in–was “much too dangerous for a young lad like you to be getting lost in at this hour of the night.” My newfound guardian walked me clear across the city to my fleabag hotel, chatting in his warm Scottish brogue, asking me about my non-existent itinerary, telling me about his grandkids, and pointing out landmarks along the way. An early one of the many experiences over the years that have instilled my faith in strangers–an experience I would have missed had I been able to simply plug my hotel into Google Maps and follow the little blue dots on the then non-existent iphone from which I’m inseparable today.

I headed for the Continent on a large ferry–probably the one that runs today from Newcastle to Amsterdam. Sitting on an outside bench along the rail of the boat, I talked for a while with a girl from Minnesota. Hillary was my age, having just graduated from Vanderbilt, about 5’6” with long dirty blond hair and grey eyes. She wore jeans and a black and gold Vanderbilt sweatshirt. Soft-spoken, friendly, and pretty, Hillary was reading The Magus, a novel by John Fowles with a bizarre cover that intrigued me (I still recall the face of a heavily made-up woman next to a rams head). Midway thru the ride, Hillary dozed off for a bit and I started reading her book, soon to be hooked by the mysterious tale that had started to unfold in the 30 or so pages I’d read when she woke up and we went back to talking. When we reached Amsterdam, where I’d intended to spend a few days, Hillary was headed for Paris. If I’d had the guts to ask, I might have succeeded in tagging along with her, as I had no particular reason to be in Amsterdam and planned to see Paris at some point. But I didn’t and, Hillary went on her separate way, toting her Magus. The kind of spontaneous decision, this one probably lousy, that–had I been bolder–could have set off a different chain of events and altered the entire trip, in one way or another, and perhaps more.

I spent much of my time in Amsterdam hanging out in pubs and playing foosball. Sometimes known as table soccer, I had effectively minored in foosball in college at Tufts. Knowing no one in Amsterdam and wondering what I’d been thinking when I embarked on this journey alone, foosball gave me an easy way to connect with other kids. I felt at home at the table–almost always with the rods controlling the two lines of offensive players in my hands and a partner I’d just met playing defense.

Although all foosball tables look very much alike, the similarities end there. I learned quickly that there are variations in both the rules and the texture of the balls used in different countries that radically alter how players can control the ball, shoot, score, and defend. I was in for a rude shock on my first day in Amsterdam when, having scored a goal with my favorite shot from the midfield, my tall, red-headed Dutch opponent abruptly announced: “You may not score from the middle; only the front line!” He offered no explanation; that was just their rule. The goal was disallowed and my stock as an offensive player plummeted.

When I wasn’t hanging out in bars playing foosball, eating frites with mayonnaise, smoking legal pot, or eating rijsttafel and playing music on my recorder with kids from the youth hostel, I scoured Amsterdam for an English version of The Magus–without success. l also failed to make it to the Dutch National Museum–the Rijksmuseum–despite trying on two successive days, thanks to a nearby basketball court to which I was glued in games with a bunch of Dutch kids.

I had more luck with The Magus in Copenhagen, a destination I chose because the schedule posted in the Amsterdam train station when I got there showed that there was an overnight train to Copenhagen departing soon (with no online schedules to check in advance on a mobile phone in those days this was how I typically “planned” my route). After finding a copy of The Magus in an English bookstore, I spent a lot of time in Copenhagen devouring it. The novel is a dark, often frightening, complicated tale about a young English man who takes a job teaching on a small Greek Island and finds himself drawn into bizarre psycho-games engineered by a wealthy Greek svengali who is unveiled to have been a likely Nazi collaborator. After 40 years, The Magus still stands out as one of the most engrossing–and perplexing–books I’ve read. Others thought so too, apparently including Fowles himself. After publishing the novel in 1965, he rewrote the baffling ending and published a revised edition in 1977.

Two events stand stand out when I think back on my time in Copenhagen. The first occurred when a gorgeous girl with thick auburn hair and brown eyes approached me as I sat on a bench reading The Magus. I had trouble believing my good fortune, as this was anything but routine given my unremarkable looks. Christine was from Munich but her English was good. I was initially thrilled when, after we’d chatted for several minutes, she invited me to a party that night at a barn just outside of the city. She said that a bunch of her friends would be there, including a man named Tobias, about whom she spoke in a glowing way. “There will be food, music and dancing, and you’ll love my friends,” she said. “And Tobias will speak to us.” I took the piece of paper she gave me with directions to the party and, after she went on her way, mulled over whether to go that night–weighing my slim chances for romance with Christine or one of her friends against some nebulous doubt that I couldn’t put my finger on. My gnawing gut won out in the end, and I passed on the party. I’ve wondered since how life might have taken a different, perhaps darker path had I decided to go that night, as I’ve suspected in hindsight that Tobias was some sort of cult figure. Another reminder of how fluke events and random choices, not well-laid plans, so often determine life’s course. And of the gambles a young person takes, or doesn’t take, especially when travelling alone.

The second memorable event occurred in my no-star hotel at around 2am. It was towards the end of June, so there was daylight In Copenhagen until well after midnight. Asleep in my room–which consisted of a single bed and a small desk with just a few feet in between–I opened my eyes in time to see a short Asian woman with long hair and glasses walking towards me. A tall caucasian man with a goatee beard stood in the half-opened doorway. The woman paused, and asked, in English: “Do you have a light?” In a daze, I said nothing but pointed to the matches on the desk. She took them, said “thank you,” and then left. I awoke the next morning unsure if I’d been dreaming, only to learn that several other guests at the hotel had been robbed. I felt a sense of relief as I thought, for just a moment, about how lucky I’d been and how different life would have looked had I slept through the robbery and awoke in the morning to find myself alone in Denmark, knowing no one, with my passport and money all gone.

On the train from Denmark to Paris I got my first introduction to Germany when, soon after we passed through the border, a patrol guard rapped on our compartment, shoved the sliding door open, and barked: “Passports!”–immediately bringing to mind stereotypical images of Nazi stormtroopers from the war that predated me but had left my mother refusing to visit Germany or buy a German car for decades. Later in the trip, I doubled back through Germany and had a rollicking night with some kids from the youth hostel at the legendary Hofbrauhaus in Munich. I doubt I knew then that this lighthearted party venue was the site of Hitler’s infamous speech to the fledgling Nazi party in February of 1920.

I arrived in Paris at night, found a cheap hotel where I shed my pack, and went out to explore the city. After bumming around for a few hours I looked at my hotel key tab to check the address. Out of luck: no address, and no hotel name. I spent the next few hours walking in concentric circles in search of my lodging (and pack). A gendarme was sympathetic and tried, but couldn’t offer much help after listening to me explain in my pathetic high school French that I’d just arrived in France and couldn’t remember the name of my hotel. He was, however, the first of many to disabuse me of the then common American notion that the French were unfriendly. I stumbled upon my hotel–appropriately named “L’Hotel”–sometime in the middle of the night.

I visited some of the iconic Paris sites and spent an afternoon outside the city at Versailles, including a classic but lonely French lunch in the woods, consisting of a plastic jug of cheap red wine to go along with a baguette, ham, and some brie. One of those times when I wondered what I’d been thinking when I set off on this voyage alone. But back in Paris life was good again. I played some foosball–with a softer ball than I was used to, but at least I was allowed to shoot and score from midfield, and had fun with the kids I met.

My foosball tour of Europe continued in Austria. After a few days in Switzerland (Bern and Lucerne), I caught a train to Salzburg, intending to stay for just an afternoon–and for the sole purpose of sampling Austrian pastry. Salzburg was the only stop on my journey where I was on a schedule. I needed to get to Rome on time to meet my college friend Ugo, who lived there. I never got to taste the pastry, as I spent the afternoon playing foosball in a small cafe/bar against a quiet Austrian guy who beat me mercilessly. I also missed my train to Rome.

When I finally made it there, Ugo picked me up on his motor scooter and drove me and my pack through Rome’s chaotic traffic to his family’s apartment. Lunch with Ugo’s family was memorable. They owned a small farm in Orvieto–about an hour-and-a-half from Rome. From what I could tell, it was devoted to producing everything one could want for a great meal: especially wine, prosciutto, figs, and olive oil. Ugo’s dad came home from the office for lunch at around one, and we sat down to what today would be celebrated as a true “farm to table” feast. Everyone then retired for a long nap, after which Ugo’s dad returned to his office and Ugo and I went out to play. A highlight for me was the impromptu soccer game we joined one night in the middle of the Piazza Navona, with our cobble stone “field” bordered by the famed Bernini fountain and the cafes surrounding the Piazza where my future wife, Melissa, and I would sip cappuccinos 40 years later. I brought to bear all the soccer skill I’d gained as co-captain of Dobbs Ferry High’s inaugural 1970 soccer team that lost every one of our fourteen games, only one, our final game, by a close score (4-3).

1974 was a year of the World Cup, and I spent hours in almost every country I visited watching soccer games on small tvs in bars or set up for public viewing in shop windows that people crowded around. The unbridled patriotic passion–obsession–I witnessed dwarfed any excitement I’d known as an avid U.S. sports fan. My afternoon in Sienna was classic. After briefly visiting the iconic striped marble cathedral, I spent the afternoon on June 24th in a bar watching Italy’s national team, favored by some to reach the Cup final, play against Poland. The bar was packed with Italian men–if there was another American in there I didn’t notice, and it wasn’t the place where I would meet the woman of my dreams. The men were yelling and, of course, gesturing dramatically, with each blown scoring opportunity or Italian defensive lapse. While I couldn’t understand a word, they were obviously disgusted with their team. Italy lost 2-1 and was eliminated from the Cup. A national tragedy, with men streaming into the streets beside themselves, some in tears–reminiscent of the Kennedy assassination at home.

The last country I visited was Greece, the setting for The Magus and the place where I finally finished reading it. Like so many other kids, I reached Greece by taking the train all the way south through Italy to the seaport town of Brindisi, located on the heel of the boot. Brindisi was bustling and creepy. I walked through the streets with two girls I’d met on the train who were repeatedly groped in ways that shocked me and frightened them. From there we took the overnight ferry to Piraeus, a short distance from Athens–among a large gaggle of kids partying on the deck of the boat well into the night. A bunch of us sat in a circle, and I played along on my recorder as a few kids with guitars played and the others sang It’s only love, Hey Jude– and other mostly Beatles songs that kids from all over knew.

I spent the first night in Athens sampling both Greek national drinks–ouzo and retsina–and sleeping outside on a flat rooftop overlooking the city. After surviving one of the very few hangovers in my lifetime, I made a stop the following day at one last foosball table, this one sitting outside a small taverna on a typically sunny afternoon in late June. I played with a kid who couldn’t have been more than 12 years old, probably the owner’s son. With jet black hair in a bowl cut, bangs creeping over his eyes, he wasn’t much taller than the height of the table. And he, too, walloped me.

I spent a week on Crete, my last stop and an Island rich in antiquities. I saw none of them. I spent most of my days out on the eastern end of the island immersed in intense volleyball games with kids from an array of countries. With my funds by then depleted, the story I’ve told over the years–which I like to think has some truth to it– is that I was paid in tuna sandwiches and beer for my contributions to the modest success of my adoptive team.

But my most memorable experience on Crete–yet another that wouldn’t have occurred in today’s interconnected world–was a trek a group of us took on July 7,1974, to a small taverna several miles away. I can date it because we went to watch a 12 inch (at most) black and white TV showing the final match of the World Cup between Holland and Germany. The fare was simple–ouzo, tomatoes, olives and feta–and the rooting intense. All for Holland. The Greek resistance to the Nazis, including on Crete, was fierce. It had not been forgotten. As in Sienna, however, the result was deflating: Germany, led by its future coach, Franz Beckenbauer, beat Holland, led by Johan Cruyff, 2-1.

So that was my 1974 tour de Europe. While I may have missed some ruins or a museum here and there, I’d managed to navigate through the lows, highs, and flukes one experienced travelling alone, mostly by connecting with friendly strangers, whether at foosball tables, on the basketball court, smoking on trains, playing simple songs on the recorder, or while lost at night. In the process, I got a real taste of the countries I passed through that’s lasted a lifetime. I was off to law school the following month–the beginning of another trail I hadn’t given much thought to, that led to a life I couldn’t have imagined. This was the last of my three solo voyages. Travels for pleasure that followed would be in the company of friends, girlfriends, and then my wife Melissa and our two sons.

I suppose my stories may sound reckless, especially to those who grew up either before or after the 60’s or 70’s: A 22 year old foosballing around Europe alone on a random, spontaneous course and schedule with no hotel or airbnb booked; often lonely, getting into or narrowly avoiding scrapes, some potentially serious. A far cry from the carefully-planned solo trips in today’s “hyperconnected times” described in the recent Journal article. But my experience wasn’t uncommon in those days. Friends biked across the country or rambled through South America and Asia. We believed the world was a safe place, and roamed this country and foreign destinations free and untethered–without itineraries; bearing only our backpacks and travelling via rail passes or just our thumbs, without a lot of money, credit cards, or access to ATMs.

These early experiences taught us how to take care of ourselves–to handle risky situations when there were no adults to cushion the fall as we inevitably veered off the rails. It’s common these days for older adults to whine about the Millennials, including their work ethic–criticisms I don’t share based on my experience working with them. The inadequacy of stereotypes aside, I see in these young adults today much to admire–in some ways different from us, in others reminiscent. Many of them don’t feel bound, or want, to stick to linear career paths–like mine to a law firm partnership, which have become more elusive and less attractive in any event. They make career changes more often than we would have dreamed, or that seems prudent to us. Many pull up stakes to follow their gut without a clearly-marked game plan, often traveling the world, sometimes alone. Indeed, the Journal article reports that “Millennials seem to be leading the way” when it comes to solo travel. Like us, they seem to have a sense of adventure.

There is one big difference between us, however: Millennials are never untethered. As these budding adults travel the globe today, they have perfect information via the internet; instant, incessant email, text, Instanet and cell phone connections with parents and friends; and the emotional and often financial support to help them navigate difficult situations and bail them out when they slip. I sometimes wonder how today’s generation of young adults, including my sons, will learn to be truly self sufficient–able to take the unpredictable falls and punches that inevitably will come in this rapidly evolving, precarious world. But I suspect that’s just me displaying the anxiety of an overprotective parent into which so many of us have morphed.

If you would like to read my post about traveling through Europe in simpler times, click here.

an enjoyable read once again, Richard. I never did go off to Europe in my younger years like you did but it sounds like it was a great adventure and learning experience for you. I do recall however hitchhiking up to Cape Cod and Martha’s Vineyard a few times and thinking nothing of doing so with just a pack on my back and not much money in my pocket. crazy to think back on that, as today you don’t see hitchhikers anymore. but we all felt safe n those days during the time of peace, love and hippiedom.

my son on the other hand has ventured off to Europe (and South America) numerous times on his own to explore or live with a family for a few weeks to keep his languages sharp when he feels them slipping from lack of use stateside. but I would suspect it’s a bit easier if one speaks multiple languages that feeling sort of lost while others talk in a foreign language other than English. it’s cool that you got into some hoops games (an international language of sorts) but surprised how much foosball sounds like it was part of your trip.

from my perspective, you’re right about how the younger folks today jump from one job to another more quickly than we might have. always enjoy your writings — thanks.

Oh the memories! I travelled with a friend in 1967 for four months and again in ‘68 for five months. In hostels and cheap hotels and actually stayed at the Negress in Nice. Yes you could do it on $5 a day and less. We hitched and walked and used our Eurail passes to get around. Only thing is that when I got to Rome I stayed and I’m still here.